Ospreys and Nightjars

- Tweed Valley Osprey Project Co-ordinator, Di Bennett, brings us the latest update from the nest.

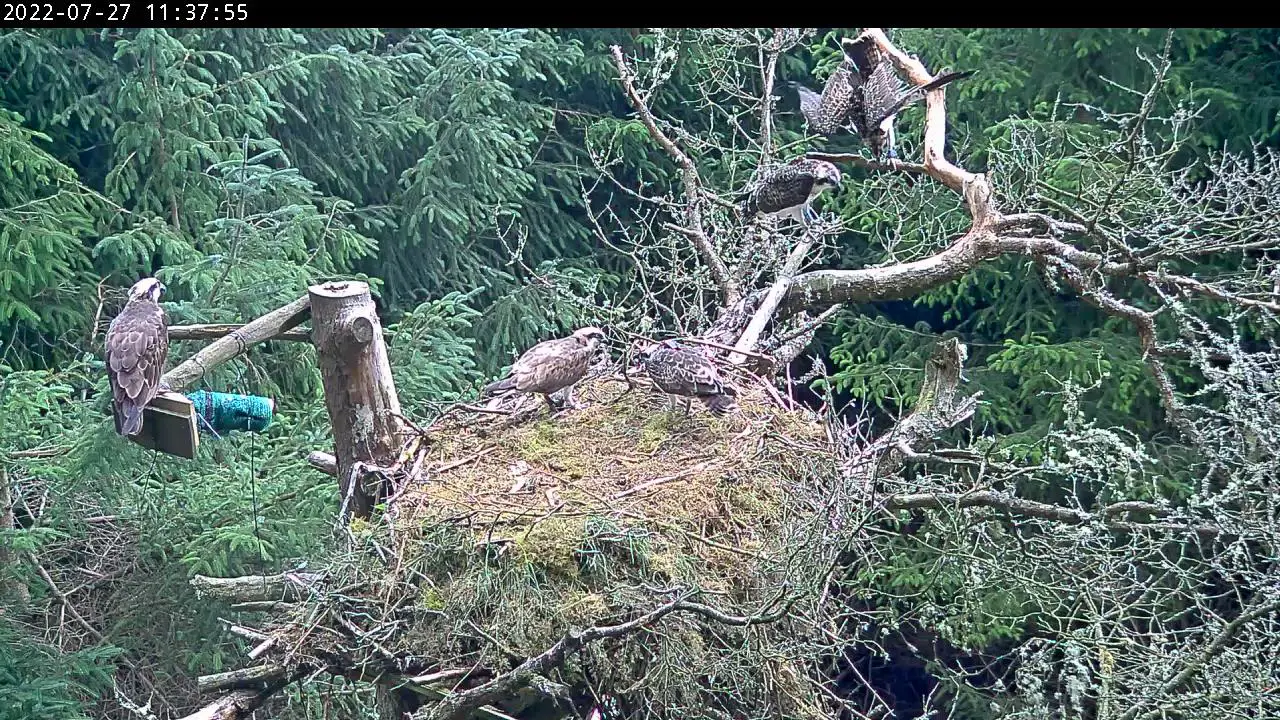

The whole family at the nest – a rare scene now

At the main Tweed Valley Osprey nest this past week we have witnessed the growing independence of the chicks as they become young adults. They are now adult sized and all three can fly. Daily honing of their take-off and landing skills provide ever increasing experience and confidence.

A young osprey flying back to the nest and his siblings watching

Sometimes it can be difficult to tell them apart from the adults when they are all present on the nest, but the plumage of the juveniles is very pretty compared to the overall drab brown of the adults. The juveniles have each brown feather fringed with a golden buff colour, and ginger colouring can still be seen when the wind ruffles the back of their neck feathers. The tracking data reveals that none of the young ospreys have left the forest yet and haven’t strayed much beyond a boundary of about 400 metres from the nest.

Mrs O feeding 707: note the difference between the adult and juvenile plumage.

Mrs O is still with the family but the intensity of her parenting is lessening and she will sit apart from the young, often to the side of the nest, but within distance to watch them without having to stay on the platform. PW3 has noticeably reduced his frequency of bringing fish into the nest. He has been such a regular provider throughout the season, he must be reducing his visits to entice the young to move further off site. One of the juveniles was seen at the top of a lopped pine, eating his fish on 29 July, and yet the exchange from father to son didn’t happen on the nest. He was learning to handle the prey himself while balancing on the top of a tree, and to feed himself.

706 and 707 with Mrs O

Occasionally Mrs O has been seen feeding them as well. Both 706 and 707 were being fed by their mum on 1 August at the nest. It will not be long before she will leave her family now and hopefully PW3 will do continue to teach his offspring the essentials before they all leave.

Names for all three will be decided this week when some of the team from Conservation Without Borders will be visiting, and they will choose the names from the suggestions that we have received so far.

Nightjars

Another very exciting project that Tony Lightley and his team have been working on with Forestry and Land Scotland, over at the Lochar Mosses Complex in Dumfriesshire, is nightjar tracking. The land is part of a lowland raised bog restoration site and is currently home to approximately 80 – 85% of the Scottish population of nightjars which are an amber listed species for conservation concern.

Members of the osprey project were invited along to see the interesting work being done to track adult nightjars at their breeding grounds which will give vital information to inform future land management for the species. The project aims to use trackers to precisely identify feeding areas and habitat. The trackers record every night (the birds are nocturnal) from 9pm to 5am at a period of two-minute intervals, then the birds are recaptured and trackers removed.

The wide mouth opened; the image blurred it was so fast

Nightjars resemble mini hawks with wide gaping beaks to hoover up moths on the wing. These are detected by their large eyes and stout, sensitive bristles around their beaks. We were all thrilled to see them flying about the moss, and then witnessing them at first hand after capture in mist nets, to be fitted with trackers, or juveniles ringed with BTO rings.

Left, a tracker fitted to the back of a nightjar's neck, and right, you can clearly see the sensitive whiskers

The conservation work is intense and carried out during the short period of summer when the birds are here after migrating from Africa. They raise two broods before leaving in September to migrate south, again on overnight flights, individually or in small groups. Their presence is given away by the churring sound of the male birds at dusk as they fly about. Their cryptic plumage makes them blend in to the background and their appearance has earned them the name nighthawks or frogmouths due to the large gaping mouths. They were even curiously named as goatsuckers in medieval times as it was believed they fed from goats’ milk at night. Work to preserve habitat for this endangered species is essential for their future and is just one of the many fascinating conservation projects being carried out by Forestry and Land Scotland.

Video highlights

Keep an eye on our 2022 highlights YouTube playlist where we're uploading our favourite clips from the nest.